by Giordano Di Veglia & Melania Franzese

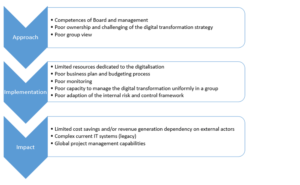

Today the digital transformation acts as a driver of profitability of banking business models. The failure of strategic projects in most cases does not depend on strategic mistakes, but on difficulties in its implementation, which are often tragically underestimated. In other words, the analysis is correct, the solutions identified are right, but the bank has not adequately assessed its ability to implement the planned changes.

The business plans show a lowest common denominator that is substantiated by the need to adopt business models based on different entrepreneurial schemes marked by digital transformation. Empirical analysis in the field, however, has shown that despite declarations of principle, every initiative in a world as articulated as that of banking companies collides with a system of significant complexity. Banking groups have stated that they are increasingly focusing on sustainable income generation, seeking to overcome structural challenges such as low cost efficiency, limited revenue diversification and, in some jurisdictions, high stocks of legacy assets.

However, balancing risk management and performance strategies is always a recipe that requires Boards to make an informed choice between the incremental approach and starting from scratch.

Within the digital transformation, in the context of the seven steps proposed in the book “Business models and profitability in the strategic banking process, focus on digitalisation”, the third step is the one that stands out, where it should be emphasised that in reality, strategic designs that on paper are flawless, have found difficulties in the execution phase, due to defects in the governance of processes.

Let us therefore try to understand the causes.

First of all, in designing the activity subject to an automation process, it is necessary to be clear that digital transformation is a refinement path of the business model that does not contemplate shortcuts, guaranteeing greater efficiency and significant profitability effects only in the medium term.

Propaedeutic to the implementation of the new processes, is the recognition of the state of the art of the complex information systems, trying to identify the trade-offs of the new technologies in business as usual.

It has been observed that, in the implementation phase of new technologies, projects often follow ‘silos’ development initiatives, without foreseeing a possible holistic use of the new technologies. For example, in the case of the development of specific tools, based on artificial intelligence, tailored to the needs of the credit area, the business cases developed generally provide for studies and applications calibrated only for that segment of operations. If the implemented processes guarantee the desired results, the failure to foresee ab origine a possible flexible use for several business segments makes it difficult to redesign the approach for other business segments as well. It is also necessary to provide for investments that take due account of the fact that some costs are in fact difficult to reduce.

In fact, it was noted in some initiatives that the projects in the ex-ante allocation of budgets had underestimated the need for continuous IT support, assuming that after the test phase and the go-live of the initiatives, strict IT governance, whether in-house or outsourced, could be disregarded. To think that the business can become computerised tout court without human intervention in the IT field, could be an implementation bias, where in the strategic design, against such savings, due consideration is not given to a prior mapping of the degree of IT knowledge of the team, which, as is known, is mostly not ‘digital native’.

The circumstance, then, that banking personnel have been subject to frequent job changes, as a result of corporate reorganisations, mergers and incorporations with consequent rapid changes in operating systems, some of which have stratified over time, makes the rapid learning of new policies and procedures based on the new IT paradigms all the more sticky.

In short, digital transformation imposes, in the writer’s opinion, organisational and governance mechanisms that in some ways can be traced back to the implementation of internal models for risk measurement, following with due parallelism the guidelines and standards published by the EBA and ECB.

It is in fact necessary, before the new business model is ‘put into production’, to:

- examine the business units, segments and channels being digitalised, especially in terms of relevant risk factors, and assess the adequacy of the model’s scope;

- verify the adequacy and adaptability of business processes associated with the new business model, including decision-making, risk management, internal control and value creation processes as well as document management;

- test technologies in a trial environment, verifying their proper functioning and ability to ‘predict’ risks (by, inter alia, back-testing and ‘trialling’ the model under various hypothetical and historical market conditions);

- assess the capacity of the IT infrastructure, the input data and the data used to ‘build’ the model;

- subject the results of the model to critical analysis and continuously monitor, by means of appropriate KPIs and KRIs, the various release phases.

Correct execution is therefore crucial to the success of one’s business model, and to operate effectively it is necessary to address this issue using a systemic approach, combining a cyclical process that aligns the organisation with the strategy and integrated management tools that converge to achieve the strategic objectives.

As a result of the performance reported in the segment reporting, the Board can assess the soundness of business execution and, taking into account how each business or geographical sector contributes to the creation/destruction of value, it can also direct the on-going strategic planning process.

To summarise then, on the basis of segment reporting, the Board will not only have to approve the strategies, but above all supervise the implementation of the strategic objectives, the related risks, and verify the implementation and the effectiveness of the strategic choices as well as overcome, if existing, the weaknesses of the strategic process and replan the fine-tuning as in a Deming cycle.

The book “Business Model and Profitability in the banking strategic process: focus on digitalisation“ deals extensively with these issues.

The opinions expressed by the authors are personal and do not in any way engage the responsibility of the institute they belong to.

Giordano Di Veglia is the Director of the Banking and Financial Supervision Department at the Bank of Italy.

Melania Franzese is an Advisor for the Banking and Financial Supervision Department at the Bank of Italy.